Pirates and Science

Pirates travelled to many places forbidden to most ordinary English sailors or royal navy captains by international treaties. This made these rovers a valuable resource for people interested in the peoples, flora and fauna of regions around the globe. Their adventures plundering around the world coincided with the rising interest in natural science embodied by the Royal Society in London. Many pirates avoided the gallows because of the detailed information they possessed.

Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America, London: 1704

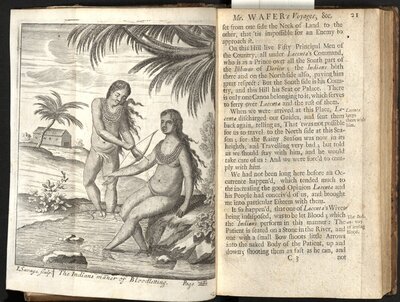

Lionel Wafer was a surgeon who joined a band of pirates who crossed over the Isthmus of Panama to attack the Spanish in what they called the “South Sea” in 1679. As they crossed back over he suffered a leg injury from a gunpowder explosion. His friends abandoned him with the local indigenous peoples. His healing abilities made him a favorite of the chief who wanted him to stay and marry his daughter. Wafer’s text is still used today by historians of medicine interested in forms of bloodletting.

Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America, London: 1699

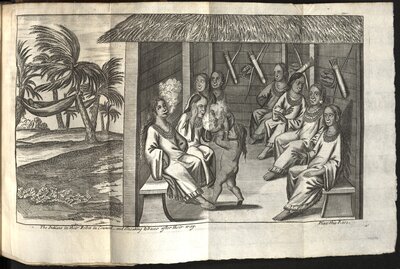

Wafer was also an early anthropologist, providing detailed depictions of Kuna Indian society and culture. Here he depicts them smoking tobacco.

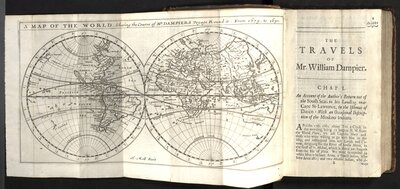

William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol. I, London: 1729

William Dampier joined English pirates in the 1680s which allowed him to travel around the world. His published journal is one of the most influential texts in the English language. Dampier can claim hundreds of words in the Oxford English Dictionary, and he was the first to describe the use of marijuana, chopsticks, and avocado and how locals ground it up with lime juice to produce an early form of guacamole.

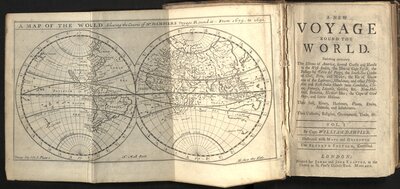

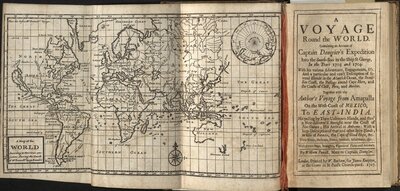

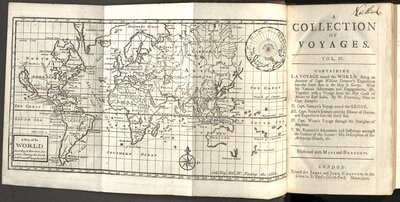

William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, London: 1698

Among the seemingly countless contributions made by William Dampier was the world map by famed cartographer Herman Moll that detailed his travels. This was one of the first world maps available and affordable to a middle class English readership. What made this map so unusual was Dampier’s refusal to simply make up information he could not confirm from personal observation or from other records. for example, rather than estimate Northern California, Dampier left the region blank.

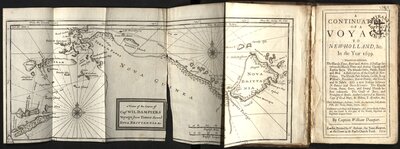

William Dampier, Continuation of a Voyage to New Holland, London: 1709

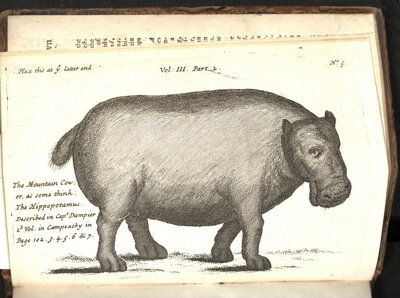

Dampier’s unique abilities to describe the world around him exemplified the spirit of late seventeenth-early eighteenth-century empirical science. Not only was Dampier fully pardoned for youthful acts of piracy, he was given command of his own vessel on an exploratory voyage to New Holland (today Australia). Here he depicts a hippo.

William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, London: 1707

William Funnell served as a mate to William Dampier on a legitimate voyage of exploration. Funnell shared Dampier’s interest in natural science, depicting here a shark and a dolphin.

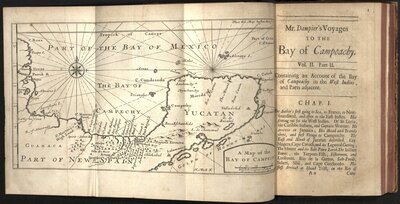

William Dampier, A Collection of Voyages… Vol. II, London: 1729

Dampier, like many other pirates, began his career cutting logwood in the Bay of Campeche. Logwood was used to die wool, the primary export of England. Although the Spanish had no need for the commodity, they jealously guarded their sovereignty over the region, periodically driving the logwooders out and forcing them into a life of piracy.

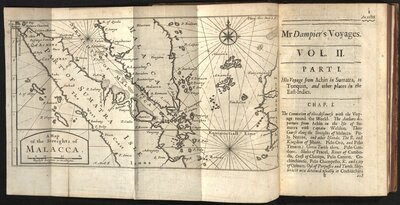

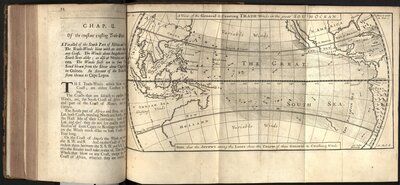

William Dampier, Voyages and Descriptions… Vol. II, London: 1699

Perhaps Dampier’s greatest contribution to a maritime world was his observation of trade winds. Benjamin Franklin avidly read Dampier’s works, influencing Franklin’s own discovery of the Gulf Stream.

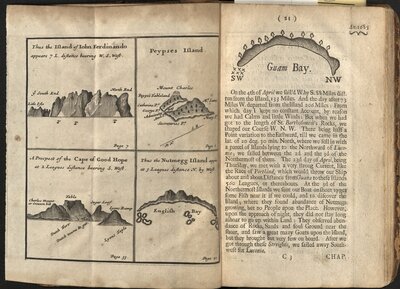

William Hacke, A Collection of Original Voyages…, London: 1699

The buccaneer journals were almost always dedicated to important noblemen associated with the Royal Society or the Royal Navy. They went so far in displaying their patriotism they named islands after English kings and queens. Here an island in the Pacific was named after Samuel Pepys, Secretary of the Navy. Here you also see the island of Juan Fernandez off the coast of Chile. This was a favorite port for pirates because it was populated with goats. This is the island where Dampier’s crewmate Alexander Selkirk was marooned providing the model for Robinson Crusoe. Today Chileans call the island Isla Robinson Crusoe.

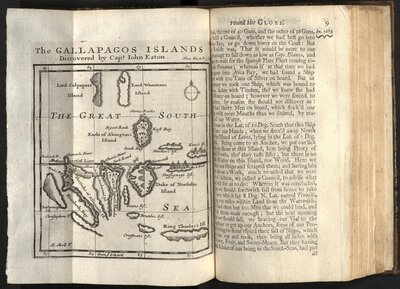

William Dampier, A Collection of Voyages… Vol. IV, London: 1729

While in the Galapagos, Dampier described turtles as being “bastard” green turtles compared to those in the Caribbean, therefore making a location- dependent differentiation between species. This was groundbreaking in that scholars at the time calculated the date of Creation in years, months, and days. The consensus established in 1658 was that the six days of Creation had begun as 9 A.M. on Monday, October 23, 4004 B.C.

While studying waterfowl in Brazil, Dampier was the first to use the term “sub-species.” Charles Darwin called Dampier’s work “a mine” of information and felt so familiar with him a century later that he referred to him as “old Dampier” in his own diary.