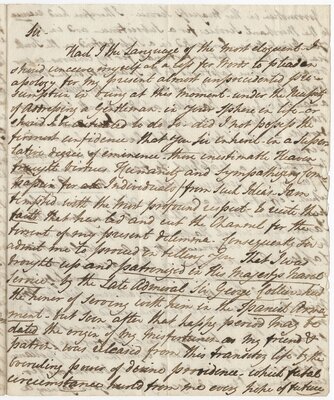

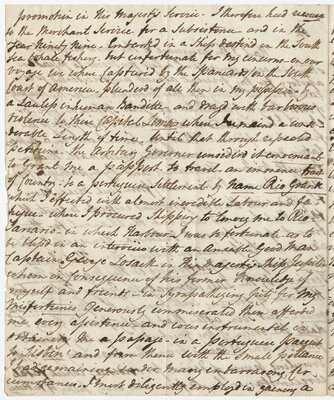

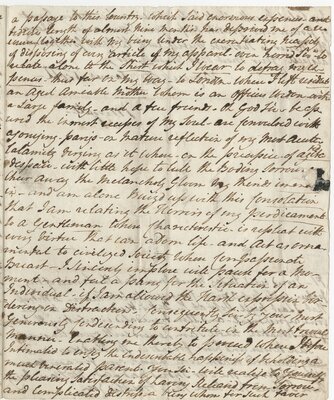

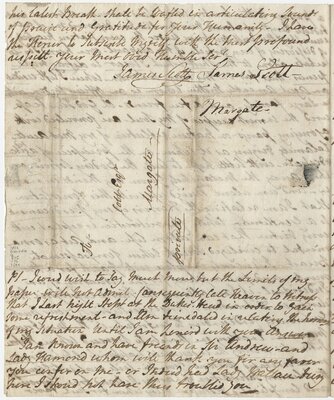

Piracy

James Scott. Letter, 1800?

Sailors were always aware that they were vulnerable to pirate attacks in foreign waters. James Scott described in a letter how he was an eyewitness to a pirate attack in 1799 off the Pacific coast of South America. Here he writes: “In the year ninety-nine embarked in a ship destin'd in the South Sea whale fishery, but... we were captur'd by the Spaniards on the south coast of America - plundered of all there is in my possession by a lawless inhuman banditti and drag'd with barbarous violence to their capital Lima.”

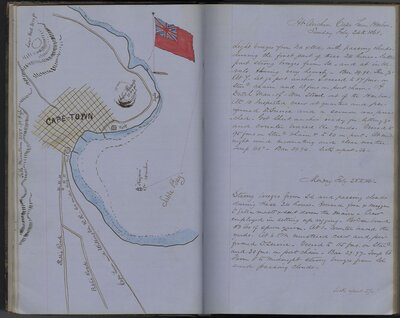

William McKean, Log of the USS Niagara (1861)

Daily routine like cleaning and maintaining the vessel kept sailors busy and not thinking about their trying circumstances. At the onset of the American Civil War, Captain William McKean, whose photo illustrates his military bearing, noted how while anchored in Cape Town harbor, he “performed d. [divine] service and a sermon was preached.”

Eugene Watson. Journal of a Cruise of the United States Brig Dolphin from New York to Madeira, and the coasts of Africa & Brazil in the years 1836, 1837, 1838 (1836-1838)

Eugene Watson was the purser on board the Brig Dolphin, a U.S. Navy vessel serving in the South Atlantic to protect American shipping and to suppress the slave trade. Although the United States abolished the slave trade in 1807 and Congress declared it piracy in 1820, this passage describes the failure of the English and American squadrons to suppress the slave trade off the coast of Africa in the 1830s.

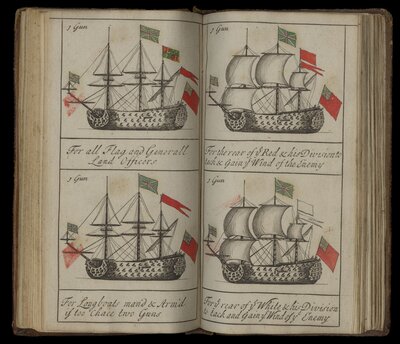

Jonathan Greenwood. The Sailing and Fighting Instructions or Signals as they are Observed in the Royal Navy (1715)

Captains used various strategies to communicate with other ships at sea, particularly in wartime. This small handbook instructed officers in the British Royal Navy on how they could use the various flags and pennants on board their vessels to communicate with their fellow warships to coordinate their maneuvers in battle. This book would have been carefully guarded to avoid tipping off enemies.