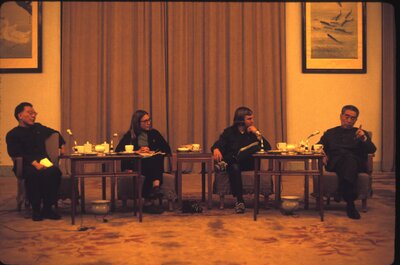

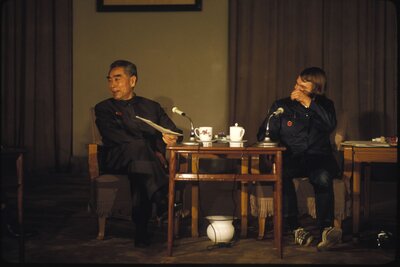

Meeting with Premier Zhou Enlai

The highlight of their China experience for members of each delegation came when they met with Premier Zhou Enlai toward the end of their trips. Though not a total surprise, as meeting with Zhou was one of their requests before they arrived, the time and location had been kept much in suspense. On July 19, 1971, they were told during lunch not to leave the hotel as an unspecified special meeting had been arranged. In the evening, the group was bused to the Great Hall of People and greeted by Zhou at the door of one of the meeting rooms. Their first impression of Zhou was that “his calm, aging face—with the bushy black eyebrows and quick, and humorous eyes—is familiar” (CCAS 1972, 294). Zhou’s relaxed and warm temperament immediately put the American guests at ease. As recalled in a 1971 newspaper article by Susan Shirk, a member of the first delegation, they were “nervous and stiff” when seeing him in person, but thrilled right away with his charming and brilliant air. When they were introduced by their self-chosen Chinese names, Zhou quickly translated back into English (Shirk 1971). He also frequently made personal references to them as individuals, a sign that he had been well-briefed and was a master of engaging guests at a personal level. During the four-hour conversation, Zhou revealed his willingness to talk with representatives of the U.S. government and reaffirmed basic principles of Chinese foreign policy. He also remarked on issues relating to Taiwan, the Indochina war, the remilitarization of Japan, and a series of current international affairs.

The second delegation’s meeting with Zhou on April 11, 1972 was arranged in a similar manner: members were notified late at night that they would meet with some Chinese officials in 10 minutes (Joseph 1972, 1). This group, unlike the first delegation, was asked not to use tape recorders or make an official transcript. In his article published shortly after the visit, Joseph proposed two main factors might have contributed to the restriction. Chinese officials may have wanted to avoid potentially embarrassing questions raised by CCAS members who were known to pose hard questions, especially regarding speculations about the downfall of Lin Biao in September, 1971. Another factor was the new escalation of the war in Indochina. Since China had not formulated an official response yet, there wasn’t much to be expected from Zhou at that time.

The meeting lasted more than four hours in a light and casual atmosphere. Similar impressions of Zhou were echoed by Joseph who recounted that “Zhou showed an amazing grasp of the details” (Joseph 1972, 11-12). He demonstrated “knowledge of special problem in a special area of the U.S.” and “a familiarity with the details of our trip in China” (11-12). Joseph described Zhou “as a man of great intellect;” his warmth and charm was unforgettable (11-12). Stephen MacKinnon, also a member of the second delegation, recalled a moment when Zhou was corrected by his staff on a fact regarding Anthony Eden’s dual role in the British government. He was surprised to see such easy exchange of ideas between Zhou and his subordinates (MacKinnon 2008, 370). In his memoir, MacKinnon vividly presented an anecdote of Yao Wenyuan, then a key member of the Political Bureau, in which he described being caught in an awkward moment of eating a piece of cream puff that got stuck on his sleeve while sitting next to Zhou.