At the Crossroads of Empire: San Diego Under Spanish Rule

With the founding of the mission and the presidio in 1769, Spanish colonization of San Diego finally began in earnest. Compared to other places in the Spanish empire, Alta California was a sparsely populated, undeveloped colonial backwater. Yet manuscripts and published materials indicate that for all its provincialism, San Diego served as the crossroads for a variety of peoples and cultures. Merchants from many nations sailed along the California coast trading with the native peoples for hides and tallow, while Spanish sailors brought much needed supplies to missionaries and settlers from as far as the Philippines and India.

Antonia María de Bucareli y Ursúa,

[Manuscript letter, signed from the Viceroy of New Spain],

1776

The mission system took on greater significance to the Spanish crown at the end of the eighteenth century in response to territorial encroachment from Russian traders to the north. But internal problems plagued the colonization of Alta California as well, including an attack by native peoples on November 4, 1775 that destroyed San Diego de Alcalá. In this 1776 letter Viceroy Bucareli y Ursúa, the top Spanish official in New Spain, cautioned the Franciscan friars to carefully review the mission’s activities and finances in order to avoid any future problems with the native population.

[Collection of five letters relating to Father Pedro Benito Cambón, the San Diego mission, and the

importation of church decorations],

1781-82

The newly established settlement of San Diego depended on Spain to supply it with basic resources and goods. Oftentimes these mundane and occasionally luxury items came not from Mexico (a journey involving long overland trails) but arrived by ship from Manila via Spain’s Pacific empire. In this letter dated December 14, 1781, Father Pedro Benito Cambón requested a variety of items from as faraway as Madras and Bombay for both the mission and the local native population, including wax, blankets, dishware, and textiles.

Estado de las misiones de la n[uev]a California sacado de los informes de sus misioneros en fin de

diciembre de 1809

This 1809 manuscript captures the state of Alta California’s 19 missions just a year before the start of independence movements in central Mexico that eventually brought Alta California under Mexican rule in the 1820s. Baptismal, marriage, and death counts indicate that San Diego was among the more populated missions of this period.

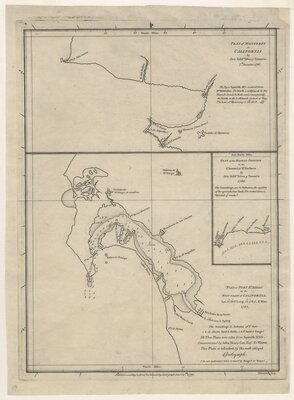

Juan Pantoja y Arriaga,

Plan of Port Sn. Diego on the West Coast of California,

London: 1789

The establishment of Mission San Diego de Alcalá and subsequent other missions, presidios, and towns in Alta California forced the Spanish crown to take a more active role in the region. Juan Pantoja y Arriaga was the pilot on the Spanish ship La Princesa, commissioned by royal officials in 1779 to bring goods and offer protection to the region’s nascent and vulnerable settlements. Produced in 1782, Pantoja’s plan is the first accurate map of the area. This 1782 English printing of his map provides evidence of the growing international interest in the area. It was followed by a French reproduction in 1797 (see wall #1). Still, the major landmarks on the map—the presidio, the mission, and two indigenous rancherías (communities) remind us that compared to other Spanish cities San Diego remained a relatively small settlement.

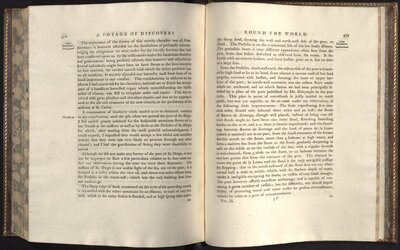

George Vancouver,

A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean and Round the World,

Vol. II (London: 1798)

Captain George Vancouver of the British Royal Navy led a celebrated expedition from 1791 to 1795 exploring the Northwest Pacific Coast as well as the Hawaiian Islands and parts of Australia. Although best known for his surveys of the region that now bear his name, Vancouver briefly stopped in the port of San Diego in 1793. Here the captain displays his seaman’s perspective of the sleepy town and the pleasantries he exchanged with the commander of the Presidio and the “Father president” of the mission to whom he bestowed “a handsome barrelled organ, which, notwithstanding the vicissitudes of the climate, was still in complete order and repair.”

![[Manuscript letter, signed from the Viceroy of New Spain]](https://exhibits.ucsd.edu/images/651-8a7a15fd0fbf2160a3aca6f1b706b823/full/!400,400/0/default.jpg)

![[Manuscript letter, signed from the Viceroy of New Spain]](https://exhibits.ucsd.edu/images/652-8a7a15fd0fbf2160a3aca6f1b706b823/full/!400,400/0/default.jpg)

![[Collection of five letters relating to Father Pedro Benito Cambón, the San Diego mission, and the importation of church decorations]](https://exhibits.ucsd.edu/images/653-38d2876acc523dbaa37c36ed20469608/full/!400,400/0/default.jpg)

![[Collection of five letters relating to Father Pedro Benito Cambón, the San Diego mission, and the importation of church decorations]](https://exhibits.ucsd.edu/images/654-38d2876acc523dbaa37c36ed20469608/full/!400,400/0/default.jpg)

![Estado de las misiones de la n[uev]a California sacado de los informes de sus misioneros en fin de diciembre de 1809](https://exhibits.ucsd.edu/images/655-38d2876acc523dbaa37c36ed20469608/full/!400,400/0/default.jpg)

![Estado de las misiones de la n[uev]a California sacado de los informes de sus misioneros en fin de diciembre de 1809](https://exhibits.ucsd.edu/images/656-408b1e0d43705af75422803cab7a8c18/full/!400,400/0/default.jpg)