California During the Gold Rush

When young New Englander Richard Henry Dana sailed to California in 1835 as a common seaman, in hopes of regaining his health from a bout of measles, he described San Diego as “decidedly the best place in California.” New England captains purchased cowhides and tallow along the California coast for manufactured goods sold to missions like San Diego. Only a few years later, American troops, bolstered by the Mormon Battalion in 1846-1847, took control of the city, raising the American flag. Two years later, gold was discovered in Sutter’s Mill, inspiring large numbers of San Diego’s inhabitants to rush northward hoping to find El Dorado. When Dana returned decades later, he lamented: “the entire-hide-business is of the past,” noting how “the beach of San Diego is abandoned and its hide-houses have disappeared.”

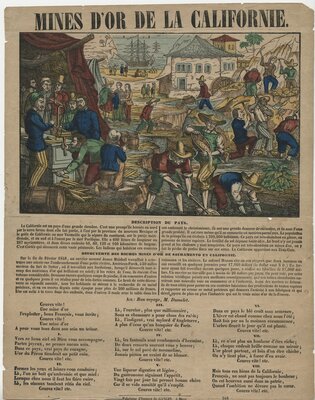

Mines D’Or De La Californie,

Metz & Paris: Dembour & Gangel, ca. 1850

This reproduction of a French broadside advertising the California gold mines claimed: “Cortez discovered this vast peninsula. The Indians who inhabit these areas have embraced Christianity, they have a great sweetness of character, and they are very truthful.” The song on the bottom calls on Frenchmen to “run quickly” to the gold mines but ends with a warning: But all these goods of California, Frenchmen, are not always happiness; One is happy also in one’s own country When ambition does not eat out the heart.

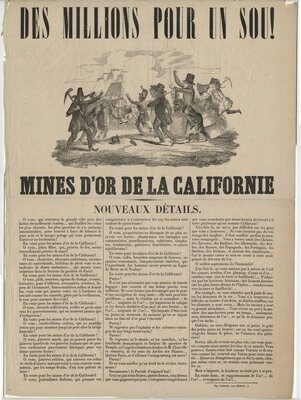

Des Millions Pour un Sou! Mines d’or de la Californie: Nouveaux details,

Paris?: 185-

“Millions for a Penny” pokes fun at the wide spectrum of French emigrants rushing to the test their luck “en route to the gold mines of California.” The author sarcastically notes the travails of the journey, the horrible reality of life in the mines, and the constant harbinger of death, all with the hope to “sit in a golden shroud for eternity.”

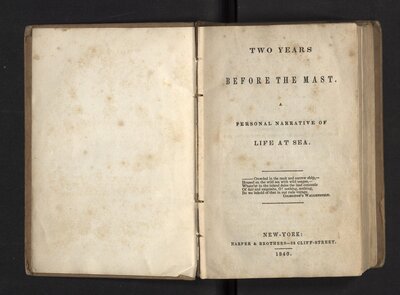

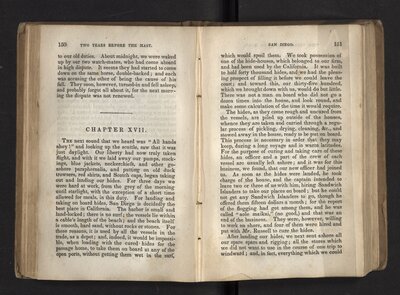

Richard Henry Dana,

Two Years Before the Mast: A Personal Narrative,

New York: Harper & Brothers, 1840

Dana’s personal account of his experience at sea and his depictions of California became an instant classic when it was published in 1840. Here Dana explains why San Diego’s landlocked harbor and the smooth hard sand of the beach made it perfect for facilitating the hide trade. He explains: “for these reasons, it is used by all the vessels in the trade, as a depot.” The trade was so lucrative that the hide-house owned by his company was easily filled with forty thousand hides. Less than a decade later the city belonged to the United States and the gold rush created a demographic transformation, leading to a dramatic decrease in trade and settlement.

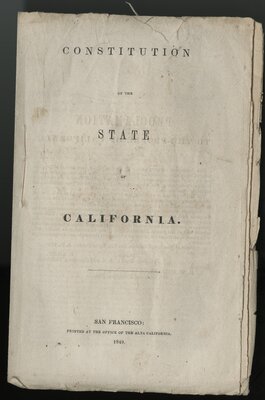

Constitution of the State of California,

San Francisco: Printed at the Office of the Alta California, 1849

This is the first printed copy of the California State Constitution. Although some southern planters called for its extension in new territories, Section 18 of Article 1, forbid the introduction of slavery in the state. Section 4 of Article 9 initiated the state’s longstanding support for public university education (including the eventual founding of UC San Diego in the 1960s) “for the promotion of literature, the arts and sciences” arguing that “it shall be the duty of the legislature…to provide effectual means for the improvement and permanent security of the funds of said university.”

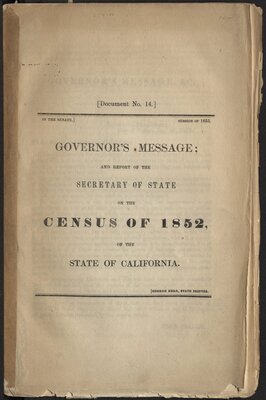

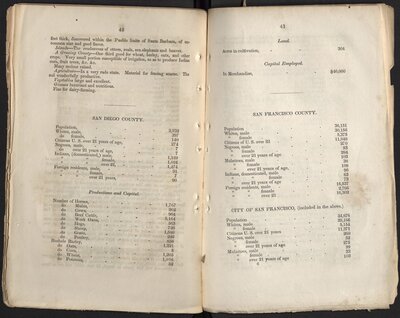

John Bigler,

Governor’s Message: and Report of the Secretary of State on the Census of 1852,

Vallejo: 1853

The 1852 census clearly displays the impact of the gold rush on San Diego’s population, with “El Dorado” luring away much of its young men. Note how a sizeable native population and older foreign men composed the majority of the male population. San Francisco faced the opposite demographic transformation.

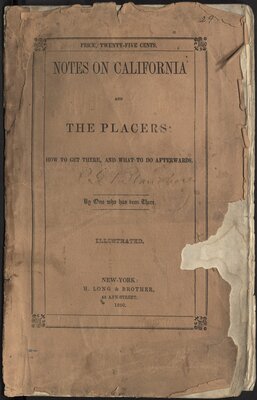

Notes on California and the Placers: How to Get There, and What to do Afterwards. By One who has been There,

New York: 1850

This text hints at the impact of male immigration from San Diego to the gold mines. According to this author: “The town of San Diego is small, situated at the head of the bay, and contains large hide-houses; hides and tallow having formerly been the principal exports of the country, until gold became the staple…It was reported that there were five hundred women in the town, and no men! The latter having gone to the diggings, consequently, we did not think it safe to land: so leaving the mail among the females, we let on steam and pushed ahead.”

William Shaw,

Golden Dreams and Waking Realities,

London: Smith, Elder and Co. 1851

English seaman William Shaw’s depiction of California was meant to “excite painful apprehensions concerning this new state of the Union” resulting from the “demoralizing effects of the California gold mania.” Here we find the socially aggressive Shaw enjoying society found in “the best sheltered” harbor “in the Pacific.” However, he also remarked upon the “large deserted hide-houses and tents” as well as “a grave-yard with numerous recent mounts.” He noted “The outskirts were principally inhabited by Indians; some of their habitations were made of adobe.” Shaw commented upon the large American flag waving in the town square with an “additional star” that “reminds the haughty Spaniards of their subjugation.” Upon the onslaught of the gold rush the port was “little frequented” yet “the greatest of simplicity of manners and habits prevails; strangers, especially if they be English, are well received.” “Availing myself of the hospitable repute of the residents, I entered boldly several houses.”

Bayard Taylor,

Eldorado, or, Adventures in the Path of Empire,

New York: George P. Putnam, 1854

San Diego was not a primary destination for gold rush immigrants, but it often served as a way station for individuals traveling from easterly routes. In this section, Taylor describes adventurers who had recently arrived in town via “the Gila route” (the Colorado Desert). He found “their clothes were in tatters, their boots, in many cases, replaced by moccasins, and, except their rifles and some small packages rolled in deerskin, they had nothing left of the abundant stores with which they left home.” He found the “stories of their adventures by the way sounded more marvelous than anything I had heard or read since my boyish acquaintance with Robinson Crusoe, Captain Cook and John Ledyard.” The Hill Collection in the Mandeville Special Collections holds first editions of each of these works.

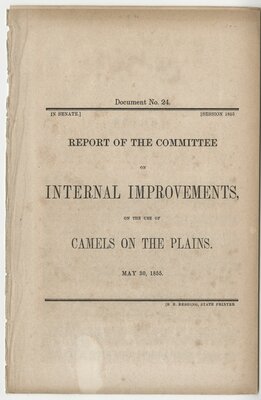

Report of the Committee on Internal Improvements on the Use of Camels on the Plains,

B.B. Redding, State Printer, May 30, 1855

The gold rush drew adventurers and merchants from all over the globe. They often crossed San Diego’s path in their journey northwards. Stories of grueling adventures across brutal desert landscapes inspired some odd suggestions. Here we find a plan to bring camels from the Middle East to help cross “our alkaline and arid deserts of Utah and New Mexico.” This promoter suggested that since “it is a conceded fact that California justly and proudly boast that she contains within her domain, some of the brightest intelligences of the present age and generation,” certainly they could come up with scheme to help manifest the “Empire of the Pacific.” This plan suggested sending “a train of dromedaries” from New Orleans to the Gila River, “thence to San Diego or Los Angeles in from eight to ten days, an almost incredible short time, yet nevertheless true.”

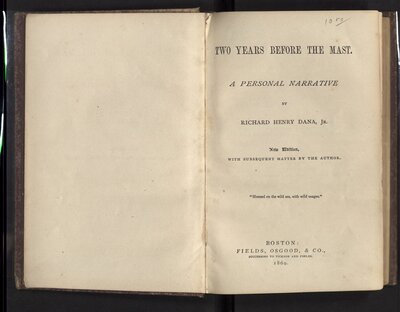

Richard Henry Dana,

Two Years Before the Mast,

New Edition (Boston: Fields, Osgood, & Co., 1869)

In 1869, Dana added an appendix to a new edition of his classic yarn entitled “Twenty-Four Years After.” He recalled once curing hides in San Diego “the year and more of beach and surf work.” “I was in a dream of San Diego…All this too, is no more! The entire-hide-business is of the past, and the present inhabitants of California a dim tradition. The gold discoveries drew off all men from gathering or cure of hides, the inflowing population made an end of the great droves of cattle; and now not a vessel pursues the—I was about to say dear—the dreary, once hated business of gathering hides upon the coast, and the beach of San Diego is abandoned and its hide-houses have disappeared.”