Mexican Rule

The Republic of Mexico became independent of Spain on September 16, 1821. Initially, Alta California remained peripheral to the new nation’s founding leaders. It took several years before the new government turned its attention towards the presidios and missions to the north. Several of these documents reflect attempts to inventory the region’s population, resources, and military strength. During this transitional period competing imperial interests continued to survey the port of San Diego, perhaps in hope of future acquisition. As the main town (currently Old Town) developed along the plaza, cowhide houses dotted the coastline of Point Loma. Yankee trader Alfred Robinson described how American merchants, intent on profiting from the hide and tallow industry, were increasingly frustrated by the Mexican government’s administrative inefficiencies. Mexico’s invitation to foreigners to settle in the region further raised the interests of American politicians bent on westward expansion, leading to the invasion of Alta California by U.S. forces in 1846.

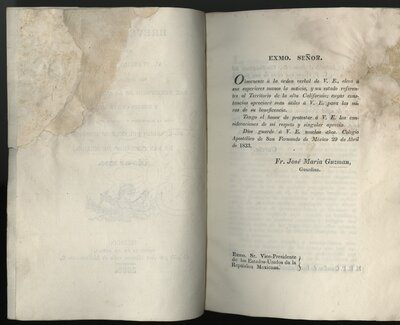

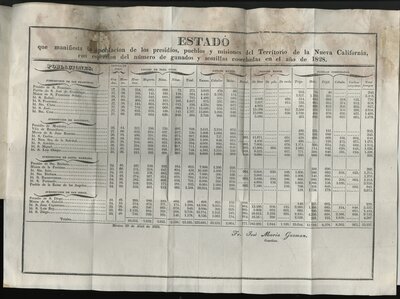

Fr. José María Guzmán,

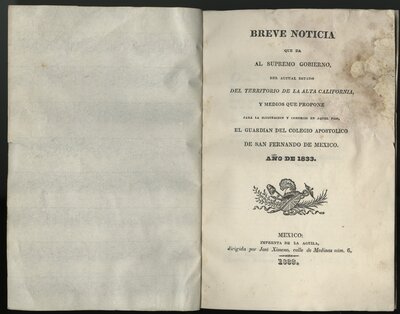

Breve Noticia que da al Supremo Gobierno del actual estado del territorio de la Alta California…,

1833

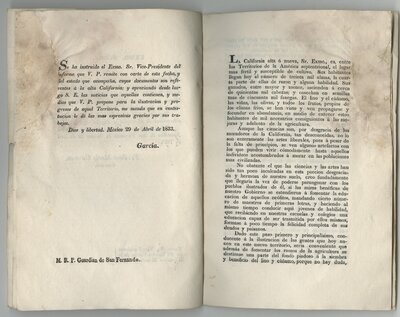

In 1833, the Mexican government requested that José María Guzmán, the head of the Franciscan order in Mexico, present an economic and social report on the state of the missions in Alta California. As part of his account, Guzmán included a census of the missions’ populations and resources from 1828. Mission San Diego de Alcalá continued to have a fair-sized population. A close inspection of the mission’s vast holdings in cattle and crops may explain why officials in California and Mexico sought to secularize them and appropriate their resources.

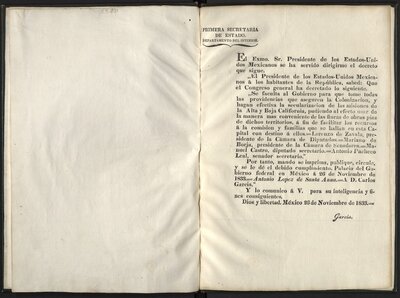

Antonio López de Santa Anna,

El Exmo. Sr. Presidente de los Estados-Unidos Mexicanos…,

1833

Calls to secularize—or remove the missions and native peoples from the control of religious orders—began fairly soon after the establishment of Mexican rule. Local officials and long-term settlers argued that their disbandment would help finance the colonization of the area (see Guzmán). In this 1833 decree, the President of the Mexican Republic, Antonio López de Santa Anna, ordered the secularization of all the missions in Baja and Alta California. San Diego de Alcalá was secularized by 1835.

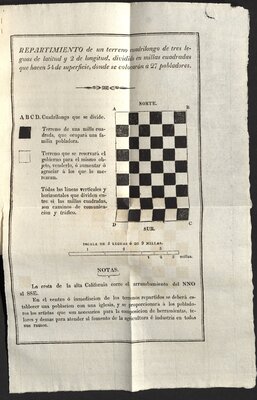

Junta de Fomento de Californias

Mexico: 1827

This book contains eight of the earliest written proposals for the political organization of California under Mexican rule, including a plan for “the foreign colonization of the territories of Alta and Baja California.” The figure on this page illustrates a proposed division of a tract of land for the settlement of twenty-seven families. Each black square represents the one square mile that each family would be allocated. Mexican officials hoped that recruitment efforts would stabilize the area. Ironically, the immigration of U.S. citizens eventually led to the loss of California (and in a few years most of the U.S. southwest) in 1846.

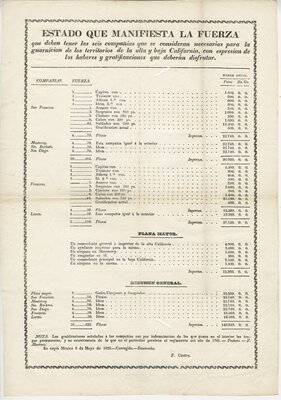

Secretaria de Guerra y Marino

Estado Que Manifiesta La Fuerza…

Mexico: May 8, 1828

Concerns about incursions and the evasion of customs regulations by foreign merchants like those described by Alfred Robinson perhaps inspired a closer inspection of military forces in Alta California. This is an inventory of the state of California’s war and naval resources including the Presidio of San Diego. Expenses included a sangrador (a “bleeder”)

Alfred Robinson,

Life in California: During a Residence of Several Years in that Territory…By an American,

New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1846

Merchants from many nations traded for hide and tallow along the California coast, including the U.S. merchant Alfred Robinson. He describes how eager Mexican officials were to trade with American ships in San Diego during the 1820s but despairs over poor administration and confusion over customs duties and trade regulations. Here Robinson describes “a small shanty in an unfinished state” intended to be a Customs House that had to be abandoned and the failed construction of a “new Presidio.” He laments: “These two monuments of the imprudence and want of foresight of the Governor, served as very good evidence to me of the want of sagacity and energy of the government.”

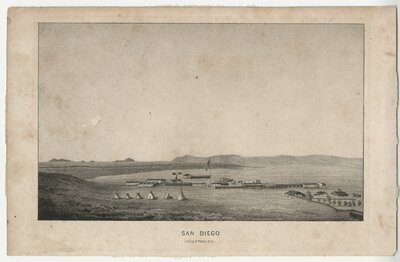

San Diego,

Baltimore, MD: Edward Weber & Co., [1846?]

The Stars and Stripes at the center of this undated image of San Diego dramatically illustrates its recent incorporation into the United States’ westward empire. The Mormon Battalion arrived in San Diego in January 1847 after an almost 2,000 mile march from Iowa to help secure the port for the United States. Today, The Mormon Battalion Historic Site visitor center operates from Old Town San Diego Historic Park.